Yes, another take into explaining SOLID Design Principles. And yes, another blog post about making your code more maintainable and readable. But this time something is different - well, mostly nothing really is (you expected something here, didn’t ya?) except that its just my perspective. A perspective gained from applying these principles in real life projects.

What is a Design Principle?

Software design principles are concerned with providing means to handle the complexity of the design process effectively. Effectively managing the complexity will not only reduce the effort needed for design but can also reduce the scope of introducing errors during design. Design Principles are standards used to organize and arrange the structural components of Software Engineering design. Methods in which these design principles are applied affect the expressive content and the working process from the start. Design principles help developers build-up common consensus about architectural knowledge, help people process with large-scale software engineering, help beginners avoid traps and pitfalls which have been detected by past experiences.

Reading the above definition might scare you if you are a beginner or confuse you if you are a seasoned developer. To explain in a concise and understandable way - the goal of a design principle is to make our software easier to understand, read, extend and maintain.

Why do we need Design Principles

Imagine you are put into a position to work on a legacy codebase that didn’t have proper code architecture and components within the projects are coupled together and you need to either fix some minor bug or extend the code with some functionality. You will find yourself jumping back and forth between individual components to understand how these individual components are coupled. Once you think you understood how the system is structured and how do these components behave (and are interconnected between each other), you start extending the codebase. But then again, while extending some of the things might not seem logical at first, so you have to adapt your mindset to follow the existing codebase, which will again force to you spend more time reading than writing code.

These issues don’t arise only on legacy codebases. Let’s say you are working for a startup (or start one of your own), and you are in charge of a project. You start your project from a clean slate and you are in charge of its architecture and the whole development cycle. We all know that startups want to release new features and new products as fast as possible, so you end up spending less time thinking about the code structure and more about just building up new features. And this is okay if you have a short-term vision for your startup. But what happens if your startup gets enough steam and is in it for the long run? How much technical debt have you introduced and how much time and money is it going to cost you while trying to scale and maintain your codebase?

Implementing these design principles is not something you will waist extra time implementing. Once you understand their meaning and their usage, gain a little bit of real-life experience, they will be part of your development process - making you a better and more-seniorish-like developer.

What does SOLID stand for

SOLID is an acronym for the first five object-oriented design (OOD) principles by Robert C. Martin, popularly known as @UncleBob.

The following 5 concepts make up our SOLID principles:

- Single Responsibility

- Open/Closed

- Liskov Substitution

- Interface Segregation

- Dependency Inversion

While some of these words may sound daunting, they can be easily understood with some simple code examples. In the following sections, we’ll take a deep dive into what each of these principles means, along with a quick TypeScript example to illustrate each one.

Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

The SRP requires that a class should have only one reason to change. A class that follows this principle performs just a few related tasks. You don’t need to limit your thinking to classes when considering the SRP. You can apply the principle to methods or modules, ensuring that they do just one thing and therefore have just one reason to change.

Lets take a look of an example where we violate SRP:

import axios from 'axios'

class User {

private emailServiceUrl = `emailService.example/api`;

private email: string;

private name: string;

constructor(name: string, email: string) {

this.name = name;

this.email = email;

}

sendGreetingEmail() {

const { name, email, emailServiceUrl } = this;

const body = `Hey ${name}. Welcome to our app!`;

return axios(emailServiceUrl, {

data: {

email,

body

}

})

}

}

const user = new User('John', 'email@example.com');

user.sendGreetingEmail();

As you can see in the example above, this User class is responsible for many things. It contains user details, sending a welcome email, contains the email service url, constructs and sends the email message. Think of the code smells here. Why would the user need to know about which email service to use? Why would the user need to handle sending a welcome email?

Lets refactor the above example so it confronts to the SRP, so we have classes (or functions) that have only one reason to change.

import axios from 'axios'

class EmailClient {

private endpoint = `emailService.example/api`

public send(to: string, body: any) {

const { endpoint } = this;

return axios(endpoint, {

data: {

email: to,

body

}

})

}

}

class User {

private email: string;

private name: string;

constructor(name: string, email: string) {

this.name = name;

this.email = email;

}

getName(): string {

return this.name

}

getEmail(): string {

return this.email

}

}

class WelcomeUserService {

private emailService: EmailClient;

constructor() {

this.emailService = new EmailClient();

}

public handle(user: User) {

const name = user.getName();

const email = user.getEmail();

const body = `Hey ${name}. Welcome to our app!`;

return this.emailService.send(email, body);

}

}

const welcomeUserService = new WelcomeUserService();

const user = new User('John', 'email@example.com');

welcomeUserService.handle(user);

When you compare the two code snippets, the refactored one is longer. So let’s address this before deep-diving into the refactor. Yes, the refactored code is a bit longer but that doesn’t mean that you will lose more time writing this code. In fact, you will save time in the long run when you go back reading and trying to understand your code. So it’s a tradeoff, and a tradeoff that you should be more than happy to make.

After we refactored our User class we ended up having three classes. Now, the User class is only responsible for keeping the user details - SRP achieved. But what happened with the other functionality? We extracted that functionality to separate classes. We have an EmailClient class, that is responsible for sending out emails (any kind of emails, not just welcome emails). Now we have a class that we can reuse now only for our users but throughout our application. The WelcomeUserService class handles sending out an email to the user when he joins our app. It is responsible for generating the body for the email and sending out the email.

There we have it. We refactored one class that doesn’t follow SRP to three classes that do. Extending any of these classes will be easier now because they are not tightly coupled.

How to notice code that needs to be refactored using SRP

- Prefixed functions that should be extracted to their own class,

- Mixing separate entities into one class (ex. encapsulating

UserandUserRoleinto one class) - Mixing separate concerns into one class (ex. encapsulating

UserandAuthServiceinto one class)

Open/Closed Principle (OCP)

People usually stop reading and trying to understand the rest of the SOLID principles after going through SRP because they feel intimidated by the definitions and names of the remaining principles, but don’t give up just yet!

The OCP requires that a class (other entities as well - functions, modules) should be open for extension but closed for modification. This principle can be confusing at the beginning because its name is counterintuitive, but once your understand it, its the principle that will save you the most time in terms of development in the future. Its goal is to get your application to a stable state, a state where the application’s core can never be broken.

Imagine we have an e-commerce application that needs to handle different payment methods. In the beginning, lets say we have a Checkout class that has a process method that processes a Cart using the payment method the user selected.

class Payment {

creditCard(cart: Cart) {

// handle payment using credit card

}

}

class Checkout {

private cart: Cart;

process() {

new Payment().creditCard(this.cart);

}

}

But, what if we want to add more payment methods - PayPal, Coupons, Bank Transfer, etc. They all have different underlying implementations, so we have to implement separate methods within our Payment class for each of these payment methods. Now, we have to add if statements within our process method within the Checkout class to handle different cases. So, if we decide to add another payment method, we have to modify our ****existing implementation to add another else if statement to handle this case. Considering this principle it means that our code design is bad and we should consider another approach.

class Payment {

private cart: Cart;

constructor(cart: Cart) {

this.cart = cart;

}

creditCard() {

// handle payment using credit card

}

payPal() {

// handle payment using paypal

}

bankTransfer() {

// handle payment using bank transfer

}

coupon() {

// handle payment using bank transfer

}

}

class Checkout {

private cart: Cart;

constructor(cart: Cart) {

this.cart = cart;

}

process() {

const paymentMethod = request().get('payment_method') // getting user's selection

const payment = new Payment(this.card);

if(paymentMethod === 'credit-card') {

payment.creditCard();

} else if (paymentMethod === 'paypal') {

payment.paypal();

} else if (paymentMethod === 'bank-transfer') {

payment.bankTransfer();

} else {

payment.coupon();

}

}

}

What would happen if we need to add another payment method? We would have to change the process method in the Checkout class and include another else if statement in the process method which violates the closed for modification part of this principle. This calls for a code design change.

To refactor this code and satisfy the requirements of the principle, we can use the Factory Pattern. The Factory pattern is a creational pattern that allows us to create different instances of a class on runtime (more about the Factory Pattern can be found online). This means that we don’t have to care about which method is going to be called because a proper class instance will be instantiated on runtime based on the client’s selection.

Knowing this, let’s refactor the example above to follow the requirements of OCP. We can define an interface and define classes for each of the payments that extend that interface and implement its methods. We will also define a PayableFactory class that instantiates our desired Payable instance and we use that in the checkout. That way, the Checkout class is not going to be modified in case we need to add another payment method and is compliant with the requirements of OCP.

interface Payable {

pay(cart: Cart);

}

class BankTransfer implements Payable {

pay(cart: Cart) {

// Handle bank transfer payment

}

}

class CreditCard implements Payable {

pay(cart: Cart) {

// Handle credit card payment

}

}

class PayPal implements Payable {

pay(cart: Cart) {

// Handle PayPal payment

}

}

class PayableFactory {

static make(type: string) {

if(paymentMethod === 'credit-card') {

return new CreditCard();

} else if (paymentMethod === 'paypal') {

return new PayPal();

} else (paymentMethod === 'bank-transfer') {

return new BankTransfer();

}

}

class Checkout {

private cart: Cart;

constructor(cart: Cart) {

this.cart = cart;

}

process() {

const paymentMethod = request().get('payment_method') // getting user's selection

const paymentFactory = new PaymentFactory(paymentMethod);

paymentFactory.pay(cart);

}

}

How to notice code that needs to be refactored using OCP

- Conditional Code - a lot of

ifelse ifelsestatements, - Multiple unit tests due to multiple execution paths,

- Violation of the Single Responsibility Principle,

Liskov Substitution Principle

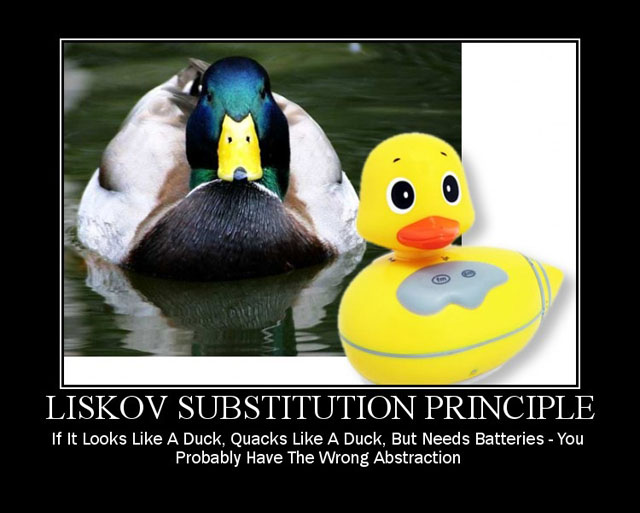

LSP states that replacing an instance of a class with its child class should not produce any negative side effects. This rule, introduced by Barbara Liskov, ensures us that changing one part of our system does not break other parts. To make this principle less confusing, we will break it down into multiple parts.

The first thing we notice for LSP is that its main focus is class inheritance. Let’s implement a straightforward and vivid example of how we can break the above principle (this time using a meme as a starting point).

Lets translate the meme to a valid OOP code.

abstract class Duck {

quack(): string {

return 'The duck is quacking';

},

fly(): string {

return 'The duck is flying';

},

swim(): string {

return 'The duck is swimming';

}

}

class RubberDuck extends Duck {

quack(): string {

person = new Person();

if(!person.squeezesDuck(this)) {

throw new Error('The rubber duck cannot swim on its own');

}

return 'The duck is quacking';

}

fly() {

throw new Error('The rubber duck cannot fly');

}

swim(): string {

person = new Person();

if(!person.throwDuckInBath(this)) {

throw new Error('The rubber duck cannot swim on its own');

}

return 'The duck is swimming';

}

}

Notice how we are changing every method of the abstract class Duck in our concrete class RubberDuck. This is the first clue that we are violating LSP. The second clue is the fly method within the RubberDuck class. It just throws an Error. This means that if we have an instance of the RubberDuck somewhere within our app and we want to call the fly method on that instance our app will fail every time, which is a signal of a bad code design.

The way we can resolve this bad code design and follow LSP is coding by contract instead of extending an abstract class. This means that our class will implement only the contracts needed for its implementation.

interface QuackableInterface {

swim(): string;

}

interface FlyableInterface {

fly(): string;

}

interface SwimmableInterface {

swim(): string;

}

class RubberDuck implements QuackableInterface, SwimmableInterface {

quack(): string {

person = new Person();

if(!person.squeezesDuck(this)) {

throw new Error('The rubber duck cannot swim on its own');

}

return 'The duck is quacking';

}

swim(): string {

person = new Person();

if(!person.throwDuckInBath(this)) {

throw new Error('The rubber duck cannot swim on its own');

}

return 'The duck is swimming';

}

}

Interface Segregation Principle

It is quite common to find that an interface is in essence just a description of an entire class. ISP states that we should write a series of smaller and more specific interfaces that are implemented by the class. Each interface provides a single behavior. It’s also important to mention that an instance (or a method) should never be dependent on methods it doesn’t use.

Let’s see through an example of what does this means.

class Subscriber {

subscribe() {

//

}

unsubscribe() {

//

}

getNotifyEmail() {

//

}

}

class Notification {

send(subscriber: Subscriber, message: string) {

// imagine we already have some EmailClient service

const emailClient = new EmailClient();

emailClient.send(subscriber.getNotifyEmail(), message);

}

}

Notice here that if the implementation of the getNotifyEmail in the Subscriber class changes, our Notification class will need to change as well even though they are not dependant on each other. To comply with the ISP, we can create an interface that implements the getNotifyEmail and have the Subscriber class implement that interface:

interface NotifiableInterface {

getNotifyEmail(): string

}

class Subscriber implements NotifiableInterface{

subscribe() {

//

}

unsubscribe() {

//

}

getNotifyEmail() {

//

}

}

class Notification {

send(subscriber: NotifiableInterface, message: string) {

// imagine we already have some EmailClient service

const emailClient = new EmailClient();

emailClient.send(subscriber.getNotifyEmail(), message);

}

}

Now, our send method within the Notification class doesn’t depend on the whole Subscriber method and only depends on the particular method getNotifyEmail in the NotifiableInterface interface.

Dependency Inversion Principle

This is the last one, I promise. The core of DIP is that high-level modules should not depend on the low-level modules. Instead, both of them should depend on abstractions. This definition is way too abstract and technical, so let’s break it down with examples and simplified explanations.

Let’s see a real-life example of DIP. Let’s say you want to charge your laptop. You can do that using your power supply adapter by plugging it into the wall socket. We don’t dig a hole in the wall to find the wirings and plug the adapter directly into our power supply grid.

To translate the metaphor above coding-wise, our interface is the socket, and it provides us with the means (functions/classes/modules) to achieve the desired outcome. This means that we don’t depend on a concrete implementation but we depend on abstractions. The most common example to take that implement DIP are database engines. You don’t care what happens under the hood, what you care about is that the abstraction provided you enough functions to read and manipulate your data.

Other benefits that this principle offers:

- Easy testing and clear boundaries of dependencies.

- Low coupling, allowing for varying implementations or business requirements changing but the contract between modules remains the same.

Let’s see this principle through an example. Let’s build a SignupService that uses an HttpClient as a data source.

// classes/HttpClient.ts

import axios from "axios";

export default {

createUser: async (user: User) => {

return axios.post(/* ... */);

},

getUserByEmail: async (email: string) => {

return axios.get(/* ... */);

},

};

// services/SignupService.ts

import HttpClient from "classes/HttpClient"; // ❌ the domain depends on a concretion

export async function signup(email: string, password: string) {

const existingUser = await HttpClient.getUserByEmail(email);

if (existingUser) {

throw new Error("Email already used");

}

return HttpClient.createUser({ email, password });

}

This isn’t ideal. We have just created a dependency from our domain to an implementation detail (HTTP) - crossing an architectural boundary and thus violating the Dependency rule. Furthermore, because signup is coupled with HttpClient, signup it can’t be unit tested.

Let’s reimplement it with dependency inversion this time! We’re going to star by decoupleing SignupService and HttpClient.

// contracts/ApiClient.ts

export interface ApiClient {

createUser: (user: User) => Promise<void>;

getUserByEmail: (email: string) => Promise<User>;

}

// classes/HttpClient.ts

import axios from "axios";

import ApiClient from "contracts/ApiClient";

export function HttpClient(): ApiClient {

return {

createUser: async (user: User) => {

return axios.post(/* ... */);

},

getUserByEmail: async (email: string) => {

return axios.get(/* ... */);

},

};

}

// services/SignupService.ts

import ApiClient from "contracts/ApiClient"; // ✅ the domain depends on an abstraction

export function SignupService(client: ApiClient) {

return async (email: string, password: string) => {

const existingUser = await client.getUserByEmail(email);

if (existingUser) {

throw new Error("Email already used");

}

return client.createUser({ email, password });

};

}

With the power of dependency inversion, our SignupService can now use any ApiClient. Let’s inject our HttpClient for now.

// index.ts

import SignupService from "services/signup";

import HttpClient from "classes/HttpClient";

const signup = SignupService(HttpClient());

signup("bojan@example.com", "password");

And there you have it. I know it has been a long article, but I wanted to share my knowledge about this particular topic for a long time.

Wish everyone a happy, productive, successful and healthy New Year & Merry Christmas!